Life & Procreation amid Ecological Concerns

“He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.”

– Friedrich Nietzsche

So, when are you going to have a baby? is quite possibly the single most dreaded and anxiety-inducing question there is to ask any childless woman, or child-free couple. Be it asked by prodding parents, impatient grandparents, distant relatives, work colleagues or even a nosy neighbour; this question is problematic for obvious reasons. Careers, residency, age, health, fertility issues, expense, income, lifestyle, timing or simply, no desire. Now we can add another response to this presumptuous question, the present and looming consequences of the climate crisis. Failing this, one can fall back on the simple yet always reliable response, It’s none of your business.

The decision to start or indeed expand your family has never been one to be taken lightly. Presently due to the unstable outlook of our future, the choice to bring new life into a damaged and dying world has become that much more burdensome. When previously before the late twentieth century, the dominant culture never had to question the certainty of the future and believed that there would always be generations to follow. Now, we cannot assume that any children, or children’s children will “walk the same earth, under the same sky.” (Joanna Macy, 1995) The childless and childbearing are ruefully asking themselves, What does it mean to bring a child into this world?

Is it in our human nature to reproduce?

From an anthropological perspective, human beings have been designed to reproduce in order to continue to flourish and avoid extinction. Evolution suggests that we must perpetuate our genes, building the ultimate panacea for human mortality. A blind force of nature, likened to all other species who roam this shared earth. Arguably forms of contraceptive methods if accessible, play a major role in challenging this idea of whether bearing a child is biologically inbuilt within our ever-changing roles as humans. Although many lack access to contraceptive technologies, particularly in developing regions which can undermine the choice to prevent or postpone pregnancy. Additionally, social constructs now dictate this evolutionary approach and offer varying proposals in relation to reproduction and whether in fact it has less to do with biology and more to do with conventionalisms that are so heavily and culturally embedded into contemporary society.

However, studies now suggest that almost half of the people living on earth are 30 years of age or younger. By 2030, this is estimated to reach 57 percent which is a worrying statistic for both modern society and future generations who will inherit the world we choose to leave them. By 2050, the even more alarming statistic is that the world’s population is expected to reach 9.8 billion, which will mean that billions of overpopulated lives will battle the environmental impact surged from our global dependency on fossil fuels. By 2050, any child born in 2022 will be 28 years of age and living in a world that will actively be seeking food, water and shelter due to global resource depletion and recurrent weather extremes accelerated by the overconsumption of developed regions. According to the United Nations, one fifth of the world could become a “barely liveable hot zone” before they turn 50, making mitigation and adaptation strategies as vital as they ever were. A child’s right to life is an inherent right that ensures a child is protected from birth and can live within the means to grow, develop, and become an adult. Similarly, the right to life promises that each and every living individual is protected. The correlation between the above statistics and the right to life provides significant apprehension. Particularly, in terms of understanding how the right to life harmonises all other fundamental human rights and simply without it have no reason to exist at all.

It is clear that climate change will consequently threaten humanity to such a defying degree that it makes me truly wonder if I was to bring a child into this world, What would that world look like? Would it be habitable? Would my child be able to grow, prosper and have children of their own? Would my grandchildren inherit a safe world? Would humanity be on the verge of extinction?

Antinatalism and Being Born into Existence

David Benatar, renowned pessimist, philosopher, author of ‘Better never to have been: The harm of coming into existence’ and advocate for antinatalism, promotes the provocative and controversial view that human beings should abstain from procreating entirely from an ethical perspective. This is due to the concept that life is so full of pain and suffering, that bringing a child into such a place would be morally corrupt and irresponsible. Accordingly, the sooner humanity ceases to exist, the world will become a better place.

The consent argument supports the notion that one believes it is obscene to conflict suffering without consent. When a child is born, they are born into the world without any form of acceptance or agreement. Once alive, moments of suffering are guaranteed, regrettably reaffirming the concept that having a child is not a personal choice, but in fact an ethical one.

Benatar signifies an anti-natalist standpoint by stating that “It is curious that while good people go to great lengths to spare their children from suffering, few of them seem to notice that the one (and only) guaranteed way to prevent all the suffering of their children is not to bring those children into existence in the first place.” Comparatively, what anti-natalists and the eco anxious have in common, is the shared growing mainstream pessimism of the current and future deterioration of the world in which we live.

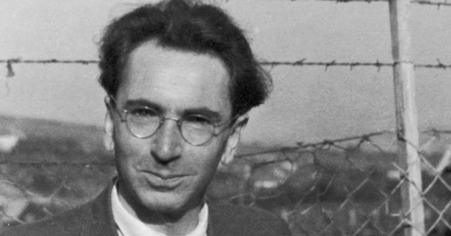

Logotherapy and the Philosophy of Life

Suffering is universal, albeit to diversified extents. Due to this inevitability, you could argue that one must attempt to find some sort of meaning in it. Viktor Frankl, Austrian neurologist, psychologist, and Holocaust survivor cultivates this concept through his belief that life is a quest for meaning and additionally the “primary motivational force in a man.” Frankl tells the story of how he survived the Holocaust through the discovery of his own personal meaning which ultimately warranted him the will to endure it. Logotheraphy, which literally means therapy through meaning was a theory inspired by Frankl’s personal ordeals as a prisoner in Nazi Germany, where he lived through four concentration camps and from it emerged the brave and innovative observation that through a search for meaning, one can endure and overcome suffering. Frankl words are harrowing and enchanting as he illustrates how “in some way, suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning.” Logotherapy demonstrates that human beings are motivated by a “will to meaning” which is consistently referred to as an analytical process. Significantly, human freedom depends on one’s response and attitude towards life’s misfortunes and life itself. Frankl’s powerful observation can be used to argue against antinatalism and provide hope for a world where suffering is inescapable.

What makes our lives meaningful? I believe that it is entirely up to us and our attitude towards the way we choose to live. Adopting a philosophy of life involves discovering how one’s life can and should be lived and ultimately unearthing what builds meaning. As a world view, this can help justify suffering, proving to be the agency of one’s lifetime. American playwright Tennessee Williams exhibits how we as human beings can strive to create our own meanings in a constantly changing world, as he famously states, “The world is violent and mercurial-it will have its way with you. We are saved only by love-love for each other and the love that we pour into the art we feel compelled to share: being a parent; being a writer; being a painter; being a friend. We live in a perpetually burning building, and what we must save from it, all the time, is love.”

Modern Parenthood and Eco-reproductive concerns

“Life is short, though I keep this from my children.

Life is short, and I’ve shortened mine

in a thousand delicious, ill-advised ways,

a thousand deliciously ill-advised ways

I’ll keep from my children. The world is at least

fifty percent terrible, and that’s a conservative

estimate, though I keep this from my children.

For every bird there is a stone thrown at a bird.

For every loved child, a child broken, bagged,

sunk in a lake. Life is short and the world

is at least half terrible, and for every kind

stranger, there is one who would break you,

though I keep this from my children. I am trying

to sell them the world. Any decent realtor,

walking you through a real shithole, chirps on

about good bones: This place could be beautiful,

right? You could make this place beautiful.”

Maggie Smith’s ‘Good Bones’, passionately and poetically envisions what it is like to love a beautiful yet broken world. Smith depicts the parallels between the good and the bad of a world that is often hard to love, one that is morally corrupt and full of hatred and horror and reveals to us how we must deceive our children and even at times ourselves to somehow try to make the world a better place.

When a child is born, the human parental instinct is heightened to protect them from all forces of danger and to shield them from the pessimistic outlook on the world in which we live. So, when one asks themselves, What does it mean to bring a child into this world? The answer can be grim, but it is vital to recognize the potential of the world we can see and the world we can still hope to create. Smith, as the realtor of her children’s lives, perseveres to show them just how beautiful our shared planet can be. She offers a plea to live in such a way that realises the present and the future, so we will no longer have to pretend or turn a blind eye, but ultimately shape and design an extraordinary and liveable world for todays and tomorrow’s children.

Feature image, credit Vanity Fair. Illustration by Neil Webb. Sourced HERE

Article: How Should a Climate Change Reporter Think About Having Children?

by Tatiana schlossberg (April 21, 2022)