Small Things with Big Lessons About Living in Community

In this moment, I don’t feel inferior or superior to anyone or anything. I’m confident in the knowledge and skills that I have, but I’m not afraid of being wrong, and I’m open to learning. I’m not trying to fix or please others. I’m simply co-enjoying the wonders of the world, alongside equals. Nature is our teacher, I am merely facilitating. I don’t feel self conscious. Their attention is not on me, but on the interconnectedness of all living things. I am aware of my needs, as they are, right now. They become simple and few, and easy to request. All my worries have vanished. I feel precious and free.

This is the peace of mind that I experience when I’m introducing humans to insects. The ideal place from which to interact with other beings.

I am a Creative Entomologist. I invented this discipline so I could follow two of my greatest passions: insects and making art. I threw caution to the wind, started a business, and hoped that the public would support this madness. They have responded enthusiastically ever since, and for this I am constantly grateful.

My mission is to reintroduce humans to their natural habitat through colourful encounters with bugs. So far, this has included workshops, school visits, nature walks, ecological surveys for conservation management, teacher training, and participatory arts projects with a focus on biodiversity, including human diversity. I want to share the power that small things possess. They can teach us and transform us.

During the pandemic, I saw a need in myself and others for localised, small scale, cultural activities that could take place within the restrictions. The purpose would be to build community, connect with nature, and facilitate creative expression for mental wellbeing and resilience. Both the artist and the target audience were low on bandwidth during this time, so interventions needed to require minimal effort. It was necessary to embrace the reality that they would have low impact and that encounters would be brief.

I received a grant from Creative Ireland, via Offaly County council, to explore this work at Coole Eco-Community, where I lived for nine months during the pandemic. Later, The Arts Council awarded me funding for a mentorship with Bee Time, “A research and artistic creation group that understands its work as a tool for change that acts by emitting resonances in the natural and social environment.”

Bee Time is based in the south of Spain, where bees are struggling to survive and the land is turning to desert. If our goal is to save life on earth, including our own, conventional wisdom tells us that change needs to happen rapidly and urgently. But the Bee Time artists and I are increasingly accepting, or at least considering, the idea that real transformation can only happen in tiny steps (like the evolution of the spelling minuscule to miniscule), and that most things we are powerless to control at all. On good days, I don’t see this as cause for despair, just reason to consider a new approach.

So, through a cloud of Covid anxiety and fibromyalgia brain fog, I have been fumbling about with deliberately low impact artistic experiments in the three very different locations I have called home over the past two years: an eco-community in rural Ferbane, Co. Offaly; Dublin’s lively, built up, North East Inner City; and the leafy suburbs of Mount Merrion. These homes became my Library of Communities in which to “read” about ways of being in a state of regenerative community with each other and the rest of nature.

When I joined Coole Eco-Community in June 2020, I was a fresh convert to the idea that living in small, tight-knit communities in tune with nature (as many indigenous cultures still do) can solve all of the world’s problems. Food sovereignty, shared social care, gift economy, tiny homes and big lives. It would allow us to live rich, healthy lives at no expense to the earth.

I still believe in eco-communities, and I vigorously applaud those who are working hard at bringing them about. But my experiences over the past two years have made me more realistic about the challenges we face in getting there. It seems that in many of our societies, including the one that has shaped me, our species has “evolved” away from that way of life, in an effort to survive capitalism, imperialism and the traumas that caused them and that ensue from them. Evolution is not always beneficial in the long run. Can we reverse it?

My time spent in these different communities, the creative experiments I carried out there, and the chance encounters with small things along the way, have given me so much information about those challenges and changes and my responses to them. I am struggling to process it into a clear purpose. I have always seen the different details of the world as colourful, curious, contradictory but simultaneous, and diverse but interconnected, gems. I’m unlikely to be able to start synthesising them into one homogenous reality now, as the snowflakes are still settling in the shaken up snow globe of my world. I want to start accepting my limits as well as my strengths.

With this in mind, I will start small and simple. I am working on a body of writing. Each piece will focus on a small thing that has taught me a big lesson about living in community. Over the coming three weeks, this website will host the first three pieces to be released out into the wild for your perusal. You will meet three small things that have made a big impact on me, and a glimpse into the alchemy they have each performed in my life or the lives of others.

Join my mailing list to read more about these as I write…

A Cutting

In April of this year, I obtained the cutting of a succulent plant, a living souvenir of a beautiful adventure. Cluelessly, I placed it with the cut end in water, and waited for it to provide me with roots. My knowledge of propagating plants is very limited, despite the best efforts of my dad. In the past, I have seen cut stems of mint effortlessly fill a jar of water with roots. I tried to replicate that effect with this cutting.

Instead, the stem of the plant began to wither and turn brown. I wanted to keep this living memory alive, so I turned to the communal wisdom of the internet for advice and discovered I had been caring for it all wrong. Who knew that some plants need you to tear off their leaves and deprive them of water?! It was so counterintuitive to me. I laid out the cutting and its detached foliage on tissue until it reached out spindly white roots, and then I potted it. It is sturdy now and sprouting new leaves.

This succulent taught me a valuable lesson. It is one that humans have long been trying to teach me, but often in times of chaos, so it gets lost. It is a lesson that hammered on the door of my mind throughout the pandemic but could not enter past the fear. Sometimes peacefully, quietly observing another species, one that is better at taking its time than I am, can help me to untangle my thoughts better than other members of my own species can.

The lesson was this. Different beings, coming from different places, cultures and life experiences, have different needs and expectations. It seems obvious now. I already knew it on paper, but now I feel it in my bones.

I can ask other people, explicitly, how they want to be cared for and what they need from me. More importantly, I can ask other people if they need anything from me. I can tell people if and how I like to be cared for, what I want and do not want. I can listen to advice and take it or leave it. Others have the right to do that too. I can trust my instincts and discover that I know what is best for me, or I might find that my instincts were way off, learn from my mistakes, and return to my community or God or the universe for guidance.

I have taught this lesson in Discovery Gospel Choir workshops, using the Tanzanian story of How the Monkeys Saved the Fish (see workshop resource 3). I have shaken my head and disapproved in superior tones as European NGOs try to impose Eurocentric solutions on perfectly capable communities in African countries. Yet asking these questions and voicing these requests in my own life is harder for me than I ever realised before this plant came into my life.

I fear that it could bring about conflict. I fear being inadequate to meet the needs that others might request of me. I fear that their needs might impinge upon my own. Sometimes it feels easier to remain oblivious to that which you cannot fulfil. I desperately want to keep the people I love safe and happy. I want to be safe and happy myself. Perhaps the most painful lesson I have struggled to learn over the past two years is that safety and happiness can sometimes be incompatible, especially during a pandemic.

I have obtained “cuttings” of the language we can use for discussing our needs and preferences from Selene Aswell, a Non-Violent Communication facilitator and community living consultant who lived with us for a time at Coole Eco-Community. I strongly recommend receiving some yourself. But getting these lessons to grow roots, and the words to sprout easily off my tongue in times of pressure and fear, takes repetition, practice, trial and error.

With this in mind, I now have twenty-four pots of different varieties of succulents. I gathered many of them during a training course with Bee Time, called New Eco-Narratives for Youth. The course was a transformational experience that has me questioning how the earth actually wants to be cared for and what she needs from us, if anything! Are we asking the right questions of nature and of each other in this regard?

I potted the cuttings three days ago. Now I’m struggling to wait the full recommended week that it takes for their roots to repair and become established before I water them. I want to give them affection, but they are not pets. I check on them multiple times a day. Surely no plant could last that long without water? I can barely stand an hour without water! But I resist. I must override the instinct that I know what is best for them. Instead, I focus on becoming more rooted, grounded, and connected to myself in order to grow stronger foundations for communication.

Workshop resource 3: https://discoverygospelchoir.ie/workshops/workshop-resources/

Selene Aswell: https://www.vibrantlyalive.community/about-us.html

A Noxious Weed

Spearheaded by organic farmer PJ Dooley and horticulturist Siobhán Lavelle, Coole Eco-Community in Ferbane, Co. Offaly, is a project dedicated to land regeneration and community living. There will be five adults and four children living in the community by the end of this year. Among other things, they are creating a food forest which would nourish a small community of humans for generations without much intervention.

I lived at Coole Eco-Community for nine months, the same length of time it takes to bring a new human life into the world, at a time when it was hard to avoid facing the precariousness of our lives.

During my time there, we hosted a permaculture weekend. Friends from other similar projects were invited to lend their observational skills and experience to our understanding of the land.

They put up their tents among the vegetation and together we feasted on vegetables from the garden, like merry caterpillars.

The first principle of permaculture is “Observe and Interact”.

“In observing nature it is important to take different perspectives to help understand what is going on with the various elements in the system. The proverb “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder” reminds us that we place our own values on what we observe, yet in nature, there is no right or wrong, only different.”

http://www.permacultureprinciples.com

That weekend, we spent time trying to understand the perspective of the land. We analysed soil samples, trapped moths, foraged for edible and medicinal plants, explored the topography and hydrology, even asked the land questions about its own needs, desires, and gifts as part of our relationship. Where would it like us to plant the forest? What does it love to do? What does it do best? What comes easily and willingly to it?

Kids and cows at the permaculture weekend

The day we spoke with the ragwort

The silage fields declared, with an enthusiastic flourish, that their favourite thing to do was to paint the skyline gold with bursts of bright yellow ragwort! This is a sentiment shared by many fields in the area. One in a nearby town looks like a purposefully sown and thriving crop of ragwort.

We joked about naming the community Ragwort Farm, enjoying the subversive flavour of this title. Ultimately we chickened out, for fear of attracting the wrong kind of attention from neighbours and authorities. Common ragwort, Jacobaea vulgaris, is classified as a noxious weed which, by law, must be removed from the land if requested by neighbours!

We wondered if ragwort could be a crop that would help us to “Obtain a Yield”, another principle of Permaculture. Could its fibres be woven? Could its yellows and purples and russet browns be made into dye? Could a plant that contains such a powerful toxin also contain a powerful medicine?

Not all yields are material, and we were soon to discover this through conversations with nature.

Red soldier beetle and cinnabar caterpillar on ragwort

One of my pet cinnabar caterpillars

Ragwort is the primary food source for the cinnabar moth. Its slate grey wings are daubed with spots and stripes the colour of cinnabar, a bright red mineral once used as a paint pigment. Its caterpillars display contrasting black and gold stripes to warn predators that it is poisonous, having stored up the toxins it ingests from the ragwort. To me they look very appealing, especially when they curl up in a spiral, but I certainly wouldn’t eat one. The cinnabar moth is in decline in the UK, and probably Ireland too, although evidence for these things is always less available here due to lack of recorders.

While living at Coole, one of my roles was to gather baseline data on the insect species living on the land, so that the impact of management interventions could be monitored over the coming years. I chose to survey moths, using a light trap, and gain an understanding of the food plants and habitat needs of this group to which I had not yet given much attention.

Many of the creative activities I organised at that time, to connect people with nature during the pandemic, revolved around the theme of Coole’s moths. Workshops in which people invented their own moths, a video tour of the local trees on which moths feed, and a virtual school tutorial on the heritage hedgerows surrounding the land, which support a great diversity of moth species.

I had mixed feelings about eradicating the cinnabar moth’s larval food plant from the silage fields at Coole, but it had to be done for the health of our cows. Standing fresh in a field, ragwort poses no threat, but farm animals don’t recognise it when it’s dried into silage, and the toxins it contains can kill them.

For weeks, we gouged ragwort plants out of the soil by their roots, piling them up in enormous heaps of purple, green and yellow, fading to russet brown. I gathered handfuls of the curled up stripy moth babies and placed them on stands of ragwort outside of the silage fields.

Ragwort even taller than Benji

Lou from Discovery Gospel Choir volunteers to pull ragwort

Uprooted ragwort

Pulling up ragwort is time consuming and tiring. It can be meditative, but it can also be frustrating when it takes us away from more constructive projects we would rather be working on, like growing vegetables or building compost toilets. It was also disheartening to have to attack something that supports so much insect life.

The ragwort itself looked unfazed by our offensive manoeuvres. Small individuals we had missed on our initial sweep with the pitchfork would grow defiantly to monstrous heights as soon as we turned our aching backs. Why was this plant punishing us so? Was it rebelling? Did it have a message for us? Something about the land? Or about our actions?

Michelle Heery, a shamanic practitioner, counsellor, and part-time Coole resident, suggested that we have a conversation with the ragwort. We spread out across the area of most intense growth, and spent some time parleying with the enemy.

I came to the ragwort with a personal question about whether it made sense to bring children into this disintegrating world where, even in Offaly, food production was being threatened by drought and at home I couldn’t hug my own parents for fear of killing them due to Covid.

As someone who identifies primarily with the Christian story of a higher power, I wonder if conversation with nature is a refractory prism for communicating with my higher power. Sometimes it is easier to access spiritual solutions through the beautiful gifts God has given us. Or perhaps you may think I was just having a conversation with myself. But plants are living things with knowledge too, and we know that they can communicate. I can certainly communicate two ways with my dog. So maybe we really did have a direct conversation with the ragwort.

Whatever happened, before I had even completed my question, a clear answer hit me and brought me to tears.

The ragwort told me that humans have forgotten how to rejoice in struggle.

The ragwort means no harm by turning up in such abundance. It is simply doing what living things do. Surviving and thriving, competing and cooperating, reproducing and withering, and feeding a multitude of other species in both life and death.

The ragwort holds no resentment towards us for defending our cattle. It doesn’t take our attack personally. Its resistance to our pitchforks is not an aggression. It’s a game. It is playing with us, wrestling with us, waking us up. It is uprooting us from our comfort zone.

The ragwort told me that humans are in denial of the fact that suffering, hardship, damage, conflict, sickness, and death are natural, unavoidable aspects of life.

It seemed to say that living a rich, vibrant life, as opposed to merely existing, requires putting aside our fear of these sometimes terrifying but perfectly ordinary things, for the sake of ourselves, our species, and the children we bring into the world.

If we want to live in community with each other and with nature, we may have to spend many more days wrestling with ragwort until we get blisters on the palms of our hands. There will be many tough decisions to make, between cattle and caterpillars, between safe isolation and risky togetherness.

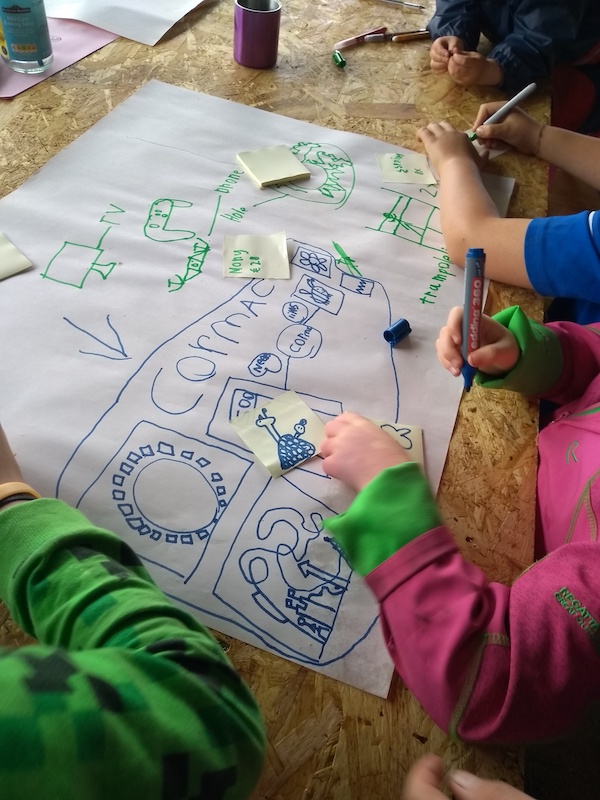

The kids make their own plans for the land

at the permaculture weekend

Permaculture participants feasting

There will be storms and there will be droughts. We will have to huddle closer together. We will get on each other’s nerves. We will argue, with each other and with the ragwort. We will fail to communicate effectively. We will react disproportionately. We will balance like acrobats in stripy leotards on the tightrope between interdependence and autonomy.

And we will all do just what we have learnt to do in order to survive, until we learn what we have to do in order to thrive. It will be a mess. A bright, beautiful, golden mess.

It is one thing hearing a message loud and clear from nature, and quite another to incorporate it into your day-to-day life and interactions. This powerful “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” medicine is a difficult pill to swallow. I have not yet ingested it like the cinnabar caterpillars have. But their clownish attire makes me laugh in admiration. I aspire to see challenging interactions as a game or a dance, as opposed to a threat. And to enter bravely into community with practicality and good humour, delighting in the boldness of my stripes.

A Song

The day after my most recent birthday, I held a workshop about Nature and Healing at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral. From maggots who clean gangrenous wounds and leeches who restore circulation, to honeybees who inspire spiritual awakenings in incarcerated men and build bridges between Israeli and Palestinian children, invertebrates offer ways to heal human bodies and minds where we ourselves have not yet succeeded.

A cricket that sings in the dry grass

A frog that sings in the forest

After exploring these amazing stories, we sang a song of healing and protection to the beehive outside the cathedral, which had been vandalised the night before.

Ama ibu o iye. Ama ibu o iye.

The extended version of this simple song contains this epic meaning:

Darkness is all around us

But the darkness is of the forest

So the darkness must be good

It is sung by the Mbuti people in the Ituri Rainforest, in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, whose culture is “entirely centred around the forest, the source of all food and protection, with a strong belief in it as a sacred place, commonly calling it mother or father.” (Song-Bar.com)

It is a traditional molimo song. A molimo is a ritual that marks a significant life event such as the death of an important member of the community. Songs are sung and music is played to awaken the forest “in the belief that if bad things are happening to its children, the tribe, it must be asleep, and must be summoned to protect them.”

The Mbuti people sing it, sometimes for hours or even days, to bring their community together in times of discord. A rousing yet soothing call that regulates the collective nervous system before facing a difficulty together. I long for every meeting I take part in to begin like this.

It is tempting to believe the description of this song’s role in Mbuti rituals is an over-romanticisation, until you hear the song for yourself. When the song is sung as a round, voices overlap and build up the sound of the rainforest, bursting with the calls of insects, birds and frogs.

It was a hit with the bored cows I used to serenade at the farm next door to Coole Eco-Community, in Ferbane, Co. Offaly. They would jostle to get a good vantage point over the fence.

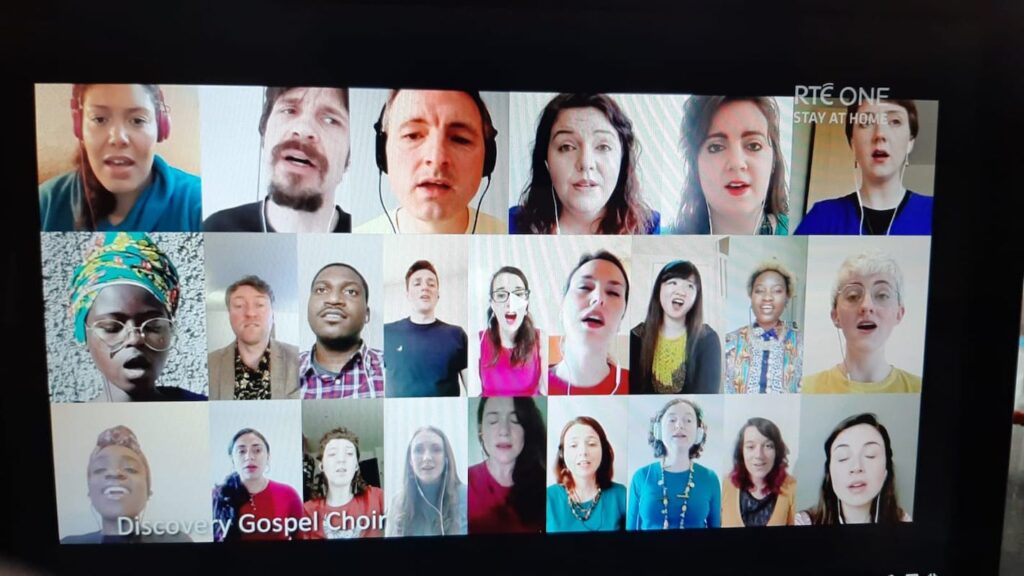

While my situation during the pandemic gave me valuable opportunities to explore life in different places and types of communities, it severed or changed my connections with the communities that had previously been most precious, grounding and supportive to me. This was an experience shared by many, worldwide. One of those communities was my choir, Discovery Gospel Choir.

When we are at full capacity, over thirty members from up to twenty-one different countries at a time come together to perform songs of joy and hope at concerts, festivals, community and church events, prisons, direct provision centres and hospitals. Our motto is Discover Beauty in Everyone.

Founded in 2014, the choir’s mission to bring people from different backgrounds together in a caring, supportive, community, is based on the tried and tested theory that working together towards a common goal can break down prejudices.

Think back to the best concert of a band or choir that you’ve ever attended. Did everyone in the audience share the exact same political and religious beliefs, skin colour, class, nationality, childhood experiences, or etiquette regarding talking during gigs? Yet, when you all sang the performers’ No. 1 crowd pleaser together, did you feel a sense of solidarity and camaraderie?

Even when we disagree on everything else, a song sung together can remind us of what we have in common, our basic humanity.

The events of the past three years threw the whole world’s communities into disharmony and division. In the Before Times, Discovery sang together in harmony every Tuesday evening. But in the During Times, we were relegated to Zoom where singing in unison, let alone in harmony, is impossible due to time lags. (Incidentally, Ama Ibu O Iye is one of the better songs to attempt in a group on Zoom, as every note works in harmony with all the others, so it doesn’t matter if we’re all out of synch!)

Against all odds, our Musical Director Carmel Whelan squeezed some beautiful virtual performances out of us, such as our Easter recording of Mangisondele Nkosi Yam, a St. Patrick’s Day collaboration with musicians in Malawi, and an entire Christmas concert! But recording the alto line for these songs alone in my bedroom (or even in a barnyard with a mischievous calf) was not the same as being together.

Snowman substitute for

a musical director

Discovery concert scene

made of snow

Discovery reunited in St. George and St. Thomas’ Church

I hungered for connection through music. Songs could help me to remember that I was living, to remember who I am, and that I still have community. I had to find ways to supplement what Discovery managed to conjure up out of the spaces between us.

I found that I thoroughly enjoy making playlists, especially when my fellow Coole residents were bravely willing to dance to them at eight o’clock in the morning. We named them after seasonal plants, such as the Ragwort, or our favourite ingredients of the week.

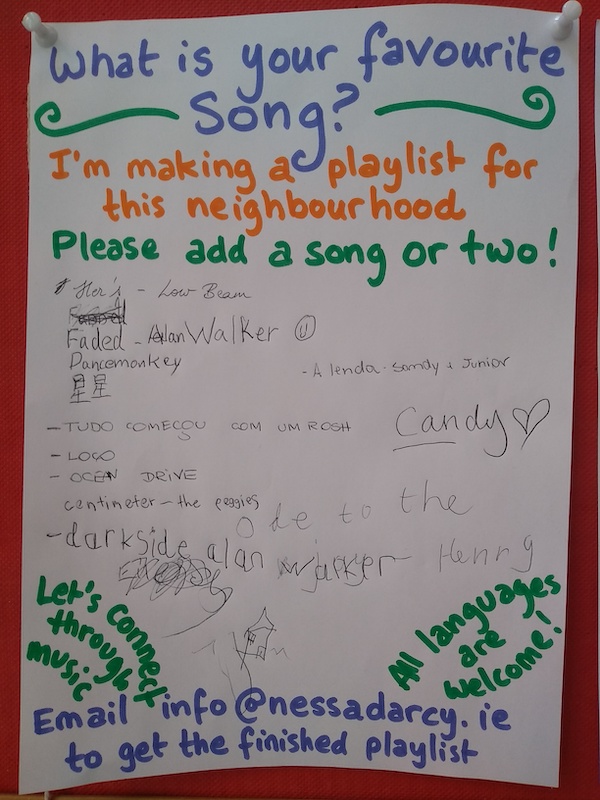

I reached out to the local community in Ferbane for contributions to add to a communal playlist. I wanted to provide people with an outlet to share creative expression and emotional connection with their neighbours despite the covid barriers. A way for them to have fun together from afar.

Two sheets of paper, which I stuck on the perspex screens at the check out desks in the local Centra, were quickly populated with song choices by young and old. They ranged from The Fureys and John Denver to Snoop Dogg and Tolü Makay. They seemed to chart the changing culture and mood of the Midlands.

I went out song-collecting where I lived in Dublin’s North East Inner City and in Mount Merrion too. I felt most at ease in the city, cloaked in anonymity, and walked from shop to cafe to park bench asking anyone and everyone for their favourite songs to listen to when they feel down.

A group of boys in Blessington Street Basin came up with the “Earworms” title, on discovering that I was an entomologist. And a man who was working out in Mountjoy Square understood what I was doing more than I did, a lightbulb appearing over his enthusiastic head as he asked if the idea was to translate the area into a music playlist!

You can listen to the playlists on Spotify here:

Earworms of Ferbane

Earworms of Mount Merrion

Earworms of Dublin’s North East Inner City

The Intercultural Ambassadors of Dublin’s North East Inner City are a group of local residents representing the incredibly diverse demographic of the area. Their aim is to “encourage active involvement by local people in promoting intercultural dialogue and addressing the barriers to integration.”

The ambassadors caught wind of my playlist project and asked me to compile a playlist of their favourite songs from their countries of origin, to celebrate the launch of their programme in Mountjoy Square.

If we can use songs to bring people together

at times of discord and fear, what other purposes can music play in the day-to-day life of a community?

What kind of songs do we need to add to our vocabulary?

I have put together an imaginary playlist of the kinds of songs that have helped me to connect with other people, other species, and myself, during the hard times and the good.

- Songs in foreign tongues that can welcome new friends and make them feel at home away from home. I may not always have something to say, but thanks to Discovery I will always have something to sing, wherever I go in the world.

- Musical first aid for people who are sick, hurting or alone. Imagine singing door to door to bring emergency creativity and joy to your neighbours. Why wait until Christmas? In Madagascar, carolling happens at Easter.

- Songs of spontaneous play and nonsense. An improvised wake up song sent by voice note that makes you laugh out loud like a happy child. Riffing off your friend’s vocal stimming (with their permission). A road trip song about a happy bunny day to make you laugh until your belly hurts.

- Memories of songs we associate with the people we are separated from (either by distance or by communication breakdown). Dad playing Moonlight Sonata when you were a child, the notes resonating through the floorboards as you fell asleep. Mum singing an impression of one of her favourite records interrupted by a scratch like a hiccup!

- Italian opera calling to neighbours from balcony to balcony, reminding them that they are not alone, and that their pain is heard and understood.

- A song of faith to fortify the family of a vulnerable young man shot dead by Gardaí outside their home.

- Sacred songs of ritual and ceremony, to mark changing seasons, marriages, deaths and births. Simple ones, easy to pick up, based on the shared aspects of our different values and faiths.

- A song with a dancing drum beat that turns an Extinction Rebellion protest into a Festival of Life.

- The rhythm of a dog’s tail beating against the oven door as you fry liver on the hob.

- A power ballad to belt out to the night sky from the back of a hero’s bicycle, in a moment of awareness of your own freedom.

- A musical number that accompanied you and your sister’s attempts at synchronised swimming on teenhood holidays in France. Play this at her 40th, the first big party since the pandemic began, to remind everyone what the Before Times felt like!

- A banshee’s keening song, to wail into the rain and wind as you stride mournfully across the fields with your black hounds.

- Raging, roaring, plate smashing songs. Alanis Morrissette and Rage Against the Machine to exorcise your heart and soul in a karaoke booth.

- A murmuration of starlings chatting and whistling about their migration path, reminding you that everything passes in time.

- The singing bowl of the sea. Place your worries into it and let go.

- A lullaby. I recommend Martian Winds Sound by Tmsoft’s White Noise Sleep Sounds. It has a post-apocalyptic vibe, as if everything has been obliterated and there’s nothing you can do about anything anymore. Now you can finally rest.

- Whatever song it is that rises naturally from your throat when somebody asks you to sing.

- A round to sing with all living things until we can hear the forest again and trust it, even in the darkness.

Winter Solstice spiral

Thank you for traveling so far with me on this experimental writing journey. I’m grateful to Ashleigh for starting this caterpillar conga line and letting me lead it for the month of August. If you would like to find out where I’m going next, join my mailing list to receive surprisingly infrequent emails about bugs and creative fun!

Nessa Darcy is a Creative Entomologist, based in Dublin, Ireland. Her aim is to promote and conserve insect wildlife and provide regenerative opportunities for humans through her ecological and artistic practices. Find out more about Nessa here.

To view all contributors: TAKEOVER Full List