Supporting Biological Diversity needs an Ethical Mindset

The smaller we come to feel ourselves compared to the mountain, the nearer we come to participating in its greatness.

Arne Næss

We face many environmental ethical dilemmas, one of which is the catastrophic loss of biodiversity. Biodiversity is the variety of living things inhabiting this beautiful Earth. The wonderful array of genes, species, organisms, and ecosystems found across the globe. In each geographical area there lives (and hopefully thrives) interacting groups of organisms and ecosystems, together creating what we call a biological (or biotic) community.

Biodiversity loss is the reduction in the variety of these ‘living beings’. It includes the decline of biological diversity, species extinction, and the breakdown of biological communities – of which we are part.

According to a report published by the WWF ‘The Living Planet Report 2020’, 68% of species across the globe have been lost in less than 50 years. Shockingly this timeline falls within one human lifecycle. Not a speckle compared to the age of Earth, estimated at ‘4.54 billion years old, plus or minus about 50 million years’. (1) Nor indeed compared to the age of our own species Homo sapiens, currently estimated at ‘315,000 years’ old. (2)

The WWF report further states, 70% of the Earths biodiversity loss is caused by agriculture, which includes the loss of approximately half the worlds tree cover. Sadly this destruction and rapid decline in biodiversity is caused by human activity and our nonchalant attitude. If we continue as we are biodiversity loss could effect all life on earth.

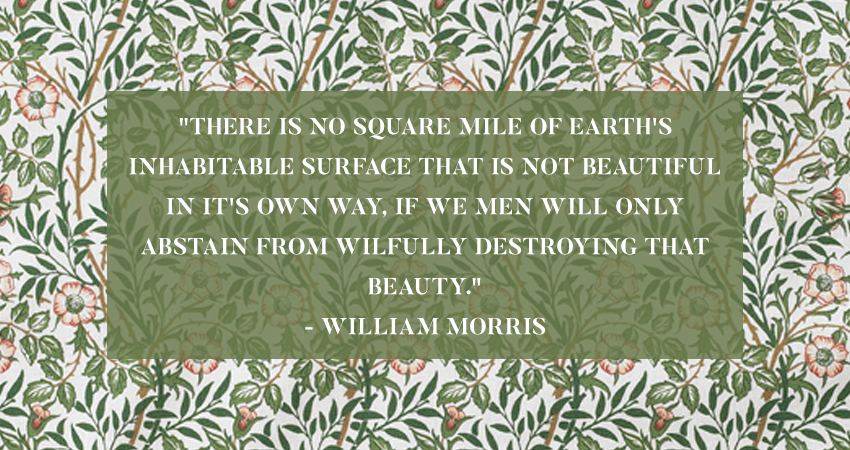

As the industrial revolution began (18th century), we were warned of the potential disasters of distancing ourselves from nature in favour of industry, mass-production and so called progress. As example the early environmentalist, British textile designer and father of the Arts and Crafts Movement, William Morris remarked ‘The century that is now beginning to draw to an end…would be called the Century of Commerce…its work has been good and plenteous, but much of it was roughly done, as needs was; recklessness has commonly gone with its energy, blindness too often with its haste: so that perhaps it may be work enough for the next century to repair the blunders of that recklessness, to clear away the rubbish which that hurried work has piled up…’. (3)

Since Morris’s observations of what economists now call the ‘First Globalization‘, we have unfortunately become more and more disconnected from the natural world. Instead of viewing our relationship to the earth as interconnected, and Homo sapiens as members ofthe biotic community, we have created a capitalist society and a guise called ‘community capitalism’ – both of which places finance and economic growth at the fore. The opposite of American philosopher Aldo Leopold’s vision of a land ethic has been applied.

A land ethic is a moral code of conduct that grows from a caring relationship for all living beings. Leopold believed ‘the relationships between people and land are intertwined: care for people cannot be separated from care for the land’. (4) In his vision of interconnectedness Homo sapiens do not conqueror (nor destroy) land for his (or her) own gain. Instead we respect and make choices for the mutual benefit of all members of the community. Unlike our current modus operandi, Leopold’s philosophy and definition of ‘community’ expands the moral patients to include the Earth as a whole, not just humans: ‘soils, waters, plants and animals, or collectively: the land’. (5)

The primary ethical challenge (or dilemma) we face in safeguarding Earth’s biodiversity is, in my opinion, human disregard for the intrinsic value of biodiversity – as a whole system.

In his 1892 lecture ‘Town and Country’, Morris said, ‘I think I may assume that… there is nobody here so abnormally made as not to take a pleasure in green fields, and trees, and rivers, and mountains, the beings, human and otherwise, that inhabit those scenes, and in a word, the general beauty and incident of nature’. (6) While I agree that most people ‘take pleasure in’ (a ‘general’ appreciation of) nature, this is not the same as feeling ‘a deep affinity with‘ nature. Seeing oneself as part of the complex web of life; not separate from nor higher than nature. Understanding ourselves as deeply rooted, entwined with nature.

Norwegian philosopher Arne Ness’ believed that ‘The well-being and flourishing of human and non-human life on Earth have value in themselves […] independent of the usefulness of the non-human world for human purposes’. (7) His principles of deep ecology are based on the belief that everything is interconnectedness, and emphasises the intrinsic value of nature for its own sake.

Similar to Leopold’s biological paradigm, based on altruism instead of egoism, deep ecology considers the living environment as a interconnected whole system which should be respected regardless of the benefits it may or may not have for humans. Ness maintained that all living beings have a basic moral and legal right to live and flourish. He distinguished two paradigms he called ‘shallow’ and ‘deep ecology’, based on a fundamental division in environmental ethics between anthropocentrism (moral values focused primarily on humans) and biocentrism (an ethical perspective that non-human life deserves equal moral consideration).

Environmental and conservation concerns consider endangered species; or how pollution and climate change is effecting the Earth’s atmosphere, the oceans and our fresh water systems; yet to-date pay little concern for the well-being of individual plants, shrubs, or invertebrates. Instead of deep ecologies understanding of our interconnectedness, we have created, and continue to create a world disconnected from (and devoid of) nature.

Ness’ believed that humans must radically change their relationship to nature from one that values nature solely for the resources it offers humans, to a value system (and moral sentiment) that recognises the inherent values of nature itself. Deep ecology suggests that environmentalism must have at its core respect and empathy for all living beings.

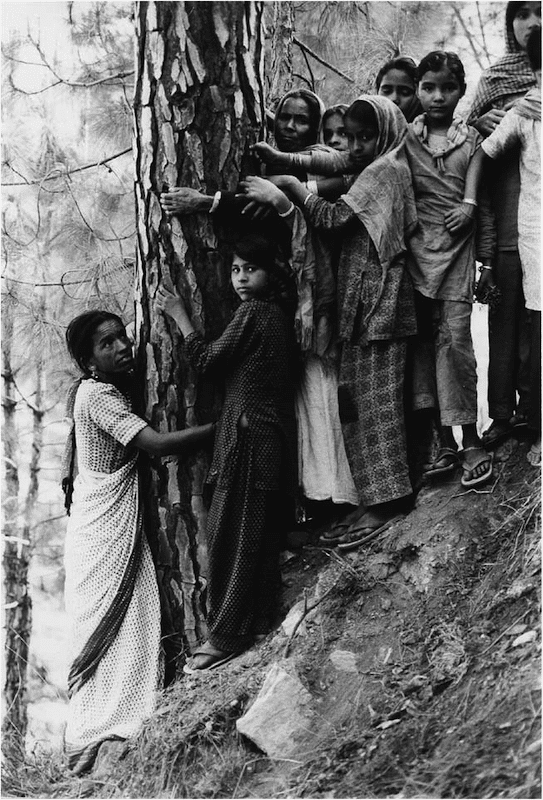

Ecofeminism represents another important evolution within environmental ethics. Similar to land ethics & deep ecology, ecofeminism is also based on the understanding of the interrelationship between humans, non-humans, and the earth. Instead of viewing nature (and the feminine) as something to dominate it sees the earth as sacred, and advocates for environmental protection and equality. It draws our awareness to the association between women and nature, and highlights societies patriarchal treatment of both.

Similar to the Gaia hypothesis, (named after the ancient Greek goddess of Earth), which understands that Earth and its biological systems – synergetic and self-regulating – behave as a single entity; Ecofeminism holds ‘a view of the world that respects organic processes, holistic connections, and the merits of intuition and collaboration’. (8)

French feminist Françoise d’Eaubonne first coined the term ecological feminisme in 1974, ‘to call attention to women’s potential to bring about an ecological revolution’. (9)

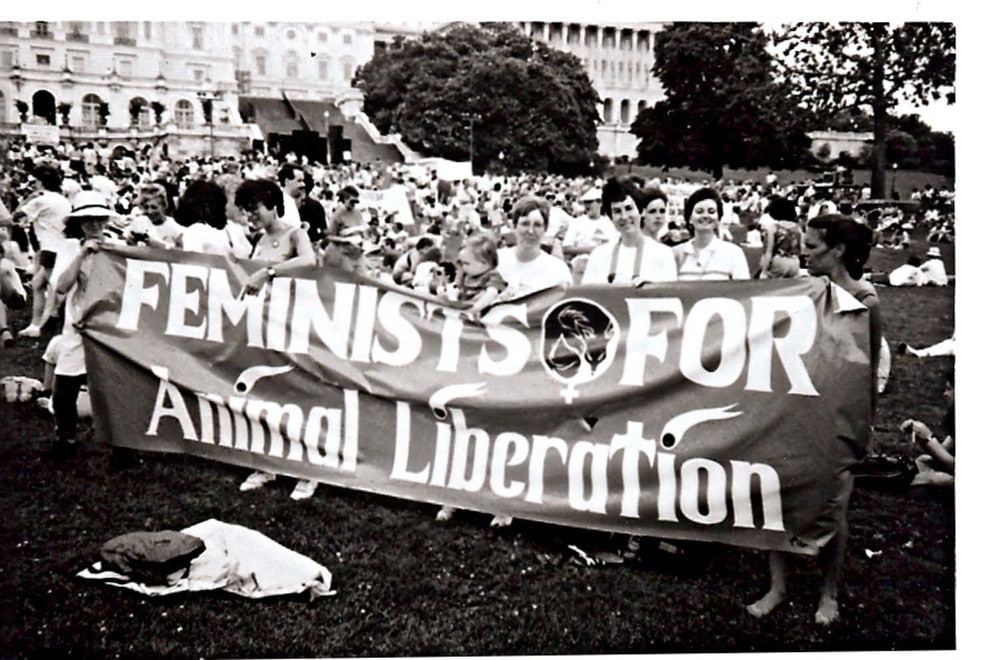

Image source: Liberty Hub, A Brief History of Women’s Liberation Movements in America

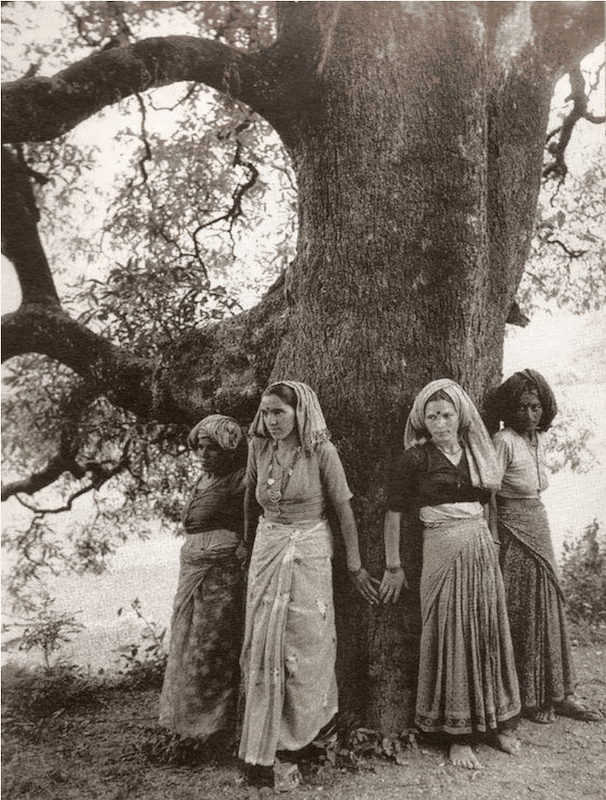

Chipko Movement: Children and women protecting a tree from being cut down (1987)

Chipko Women protecting a tree from being cut down, Northern Uttar Pradesh, India (1994)

Feminists for Animal Rights (FAR), California (1981)

Women innately understand the power of nature, and our material dependence on it. Like deep ecology and land ethics, ecofeminism recognises the fountain of energy that flows through the land, and the importance of connecting with this energy, for life on earth to survive.

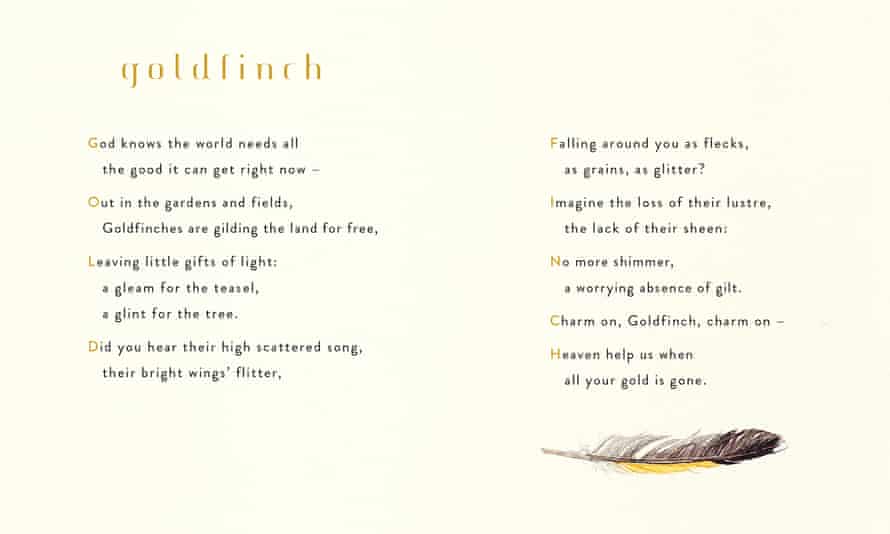

Photograph: Jackie Morris

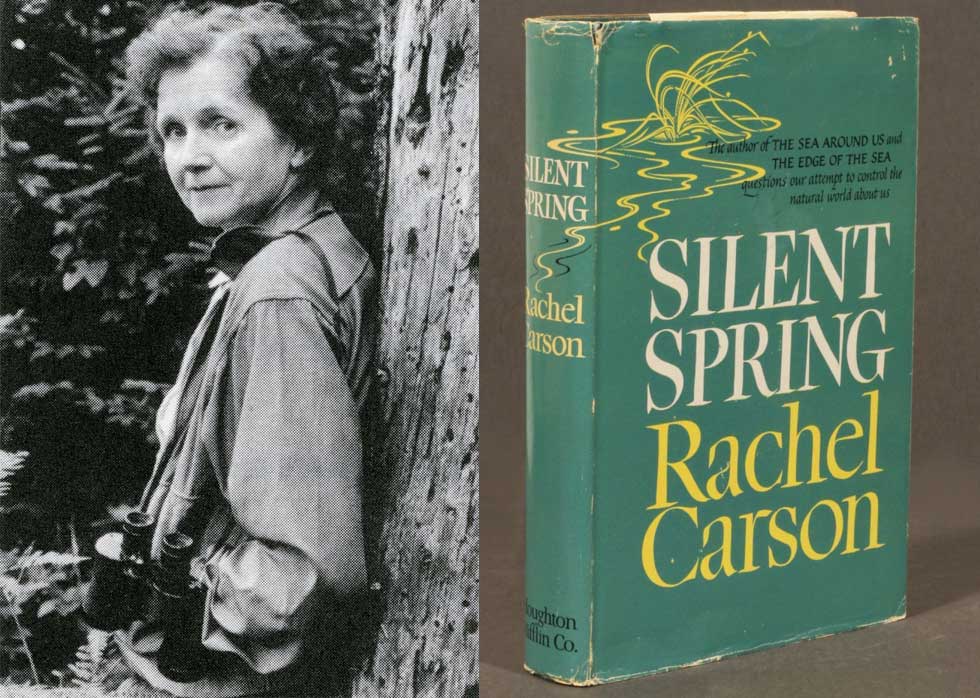

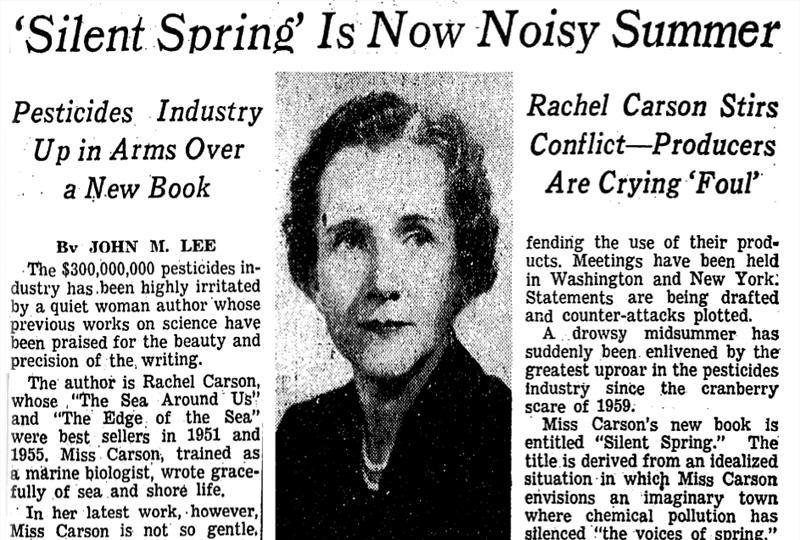

Only within the moment of time represented by the present century has one species — man — acquired significant power to alter the nature of the world.

Rachel Carson (Silent Spring, 1962)

References:

- WWF ‘The Living Planet Report 2020’

- AGE OF THE EARTH. National Geographic Society Resource Library.

https://rb.gy/uh4fbh. Accessed: 3 February 2022 - Callaway, Ewen. (June 2017), Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species’ history. Nature Briefing. https://rb.gy/zsfge1. Accessed: 3 February 2022

- Morris, M. (1966), The Collected Works of William Morris. New York: Russel & Russel, 24 (XXII), p.179.

- First Globalizations

- The Land Ethic.The Aldo Leopold Foundation. https://rb.gy/dkgh3c.

Accessed: 3 February 2022 - Leopold, Aldo. (1949), A Sand County Almanac, and Sketches Here and There. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 204.

- Morris, William. (1892), Town and Country. https://www.marxists.org/archive/morris/works/1892/town.htm. Accessed: 28 January 2022

- Naess, Arne. & Sessions, George. (1984), Basic Principles of Deep Ecology. The Anarchist Library. https://rb.gy/hburku. Accessed: 3 February 2022

- moral sentiment : The Theory of Moral Sentiments, by Adam smith

- Miles, Kathryn. “ecofeminism”. Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9 Oct. 2018,

https://www.britannica.com/topic/ecofeminism. Accessed 5 February 2022 - Warren, Karen J. (2015), Feminist Environmental Philosophy. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-environmental/. Accessed 5 February 2022

Feature image: cottonbro